Calligrapher scripts success with Arabic style

SPECIAL TO THE WASHINGTON TIMES

By Erling Hoh

A BEIJING — In this age of colliding cultures, Chen Jinhui melds two of the more ancient ones simply by using a wolf-hair brush and some finely ground Tie Zhai Ong ink.

He is a Chinese calligrapher writing Arabic script, which in his sanguine, rotund person brings together two of the world’s greatest traditions of beautiful writing.

Chinese as well as Islamic culture may revere calligraphy as the highest form of art, but in many ways, the similarity ends there. Where Chinese calligraphy is spontaneous and intuitive, Arabic calligraphy appears intellectual and infinitely premeditated.

While Chinese calligraphy can strike the eye with the liberating effect of a tempest, Arabic calligraphy exudes the cool elegance of an intricate mathematical equation. To fuse them is no mean feat, and by having done so for the past 40 years, Mr. Chen is sparking new synapses and garnering accolades all the way from Beijing to Istanbul.

Seated in his spartan office at the Institute of Islamic Theology in the southern part of Beijing, Mr. Chen, the institute’s retired librarian, is not one to dwell on aesthetic dialectics of Chinese and Arabic calligraphy. He will, however, relate the story of his hero, the famous Arabic calligrapher Ibn Mukla, a vizier in Baghdad during the Abbasid dynasty, which ruled from A.D. 750 to 1258.

“His influence was greater than the caliph’s, because of his calligraphy,” Mr. Chen said. Out of jealousy, Mr. Chen said, the caliph persecuted the Arabic calligrapher. But when the ruler ordered that the artist’s hand be cut off, he simply tied the pen to the remaining stump and continued writing.

“That is why they consider him a god. He was attacked so many times, but he never forgot his calligraphy,” Mr. Chen said.

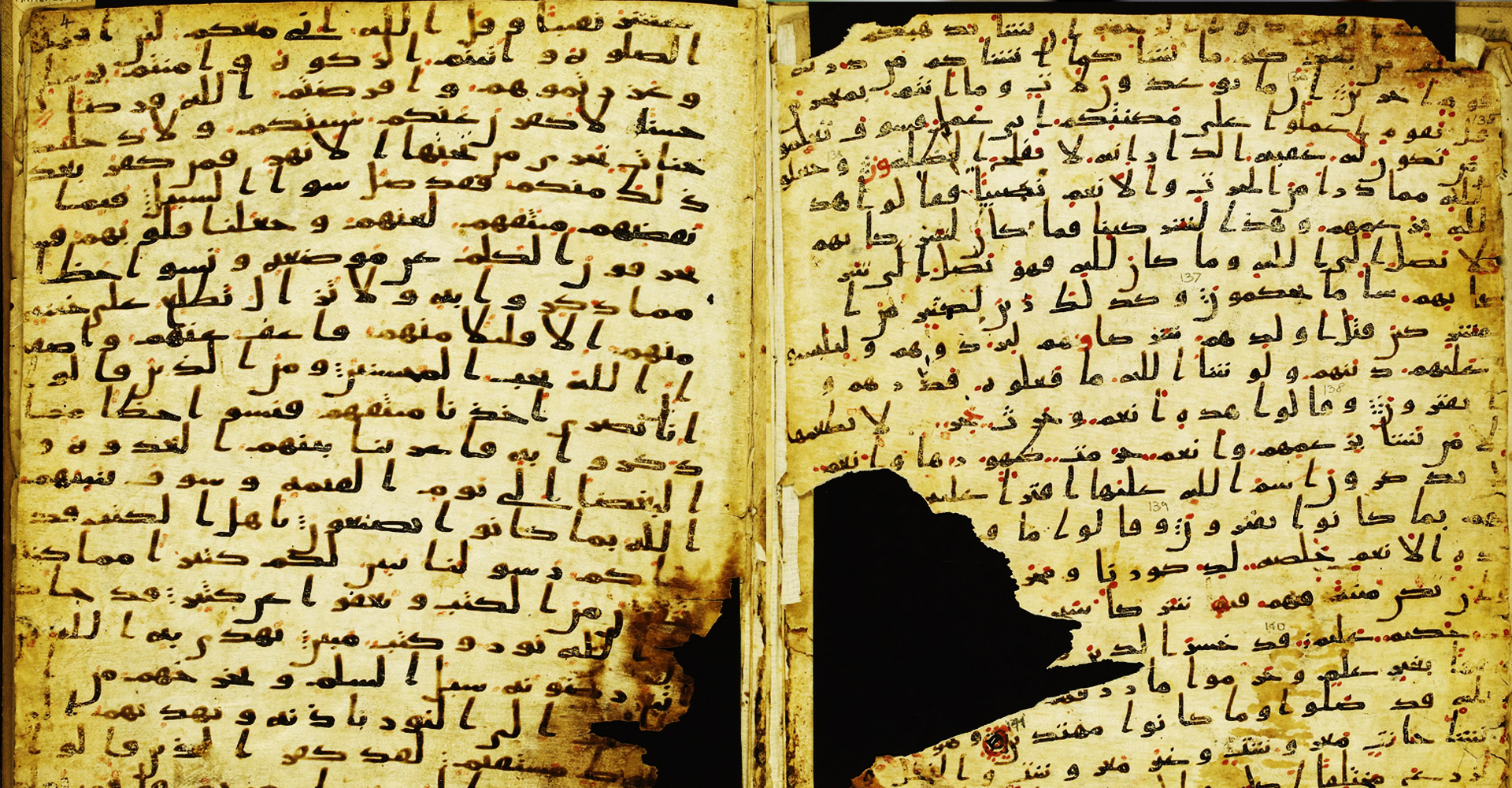

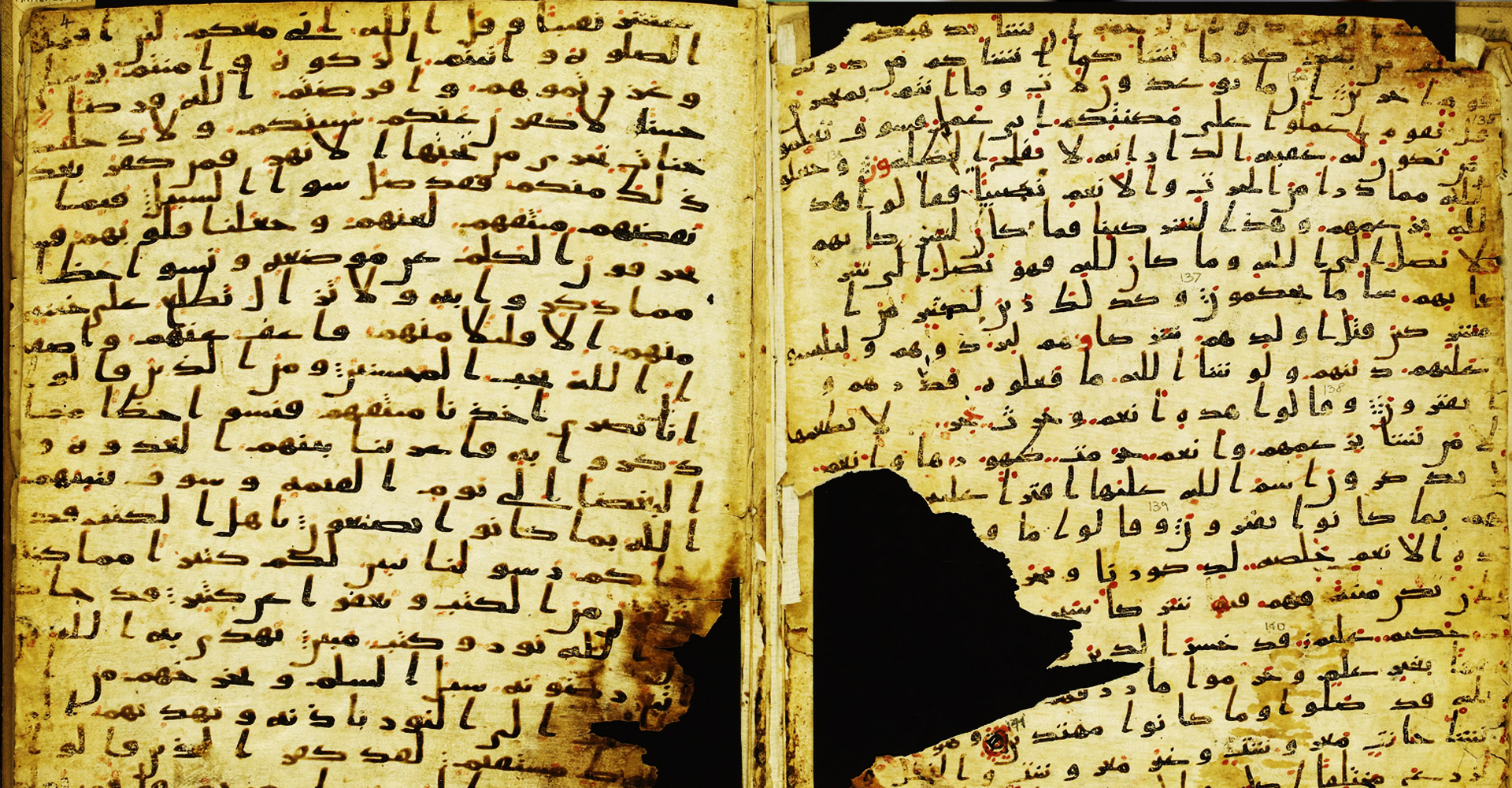

When Islam spread to China 1,000 years ago, Chinese Muslims began using the traditional brush and ink to copy the Koran. The oldest handwritten copy of the Koran in China dates to 1318. In time, an original form of Arabic calligraphy with distinct Chinese characteristics, known as Sini, evolved.

Following in the footstep of such famous Chinese Arabic calligraphers as Huababa, a Qing dynasty scholar from the province of Henan, Mr. Chen took up Arabic calligraphy as a student at Institute of Islamic Theology in the 1950s.

During Mao Tse-tung’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, however, Islam was virtually forbidden and Arabic calligraphy was denounced as part of the “four olds.”

After China reopened its doors in the late 1970s, the country’s Muslims were allowed to practice their religion and re-establish ties with the Islamic world. Mr. Chen made his first hajj to Mecca in 1989.

A year earlier, he had received an honorable mention at the first Iraqi International Festival of Arabic Calligraphy and Islamic Decorative Art, and in 1995, he was placed ninth in Kufic script at the Third International Arabic Calligraphy Competition in Turkey. His biggest triumph came when he won first prize at the Second International Calligraphy Competition in Pakistan in 1999.

In a selection of his works, published last year by China’s Nationalities Photographic Art Publishing House, Mr. Chen demonstrated his mastery of all the major Arabic styles — Thulethi, Kufic, Persian, Diwani, Diwani-jili, as well as the Sinicized Arabic script.

With his success in international competitions, his calligraphy has been attracting patrons from around the Islamic world.

“They didn’t know anything about Chinese Muslims. ‘You can read the Koran too,’ they exclaimed. They were very surprised,” Mr. Chen said about his trips to various competitions in the Middle East.

A major difference between Chinese and Arabic calligraphy is that when the art form began to evolve on the Arabian Peninsula in the sixth and seventh centuries, calligraphers there had to make do with goat skin, bark and cloth. The roughness and low absorbency of these materials might have channeled Arabic calligraphers into developing an aesthetic centered on pattern and intricacy.

In China, where paper was invented in A.D. 105, calligraphers focused their search for beauty on the rich expressive possibilities of the brush-ink-paper medium: texture and immediateness.

In A.D. 751, Arab and Chinese armies clashed in a battle on the Talas River in present-day Kyrgyzstan. The Chinese were defeated, and among the prisoners taken by the Arabs were Chinese paper makers. Having learned the art of paper making from Chinese, the Arabs transmitted the craft to Europe several centuries later.

Chen Jinhui is now busy investigating a cultural diffusion in the other direction: the history of Arabic calligraphy in China.

“It is very difficult research. I want to fill in all the blanks,” Mr. Chen said. For encouragement, he has only to recall a saying of the prophet Muhammad:

“Seek wisdom, even if it be in China.”.